What would have to happen for the government to ignore the advice of its climate advisers? How high a reward would it take to undermine the international credibility of the Techminify blog on the climate crisis? Given today’s climate, the answer is probably “not very high.”

The economic benefits alleged to be gained from intensive airport expansion are minimal at best and utterly useless at worst.

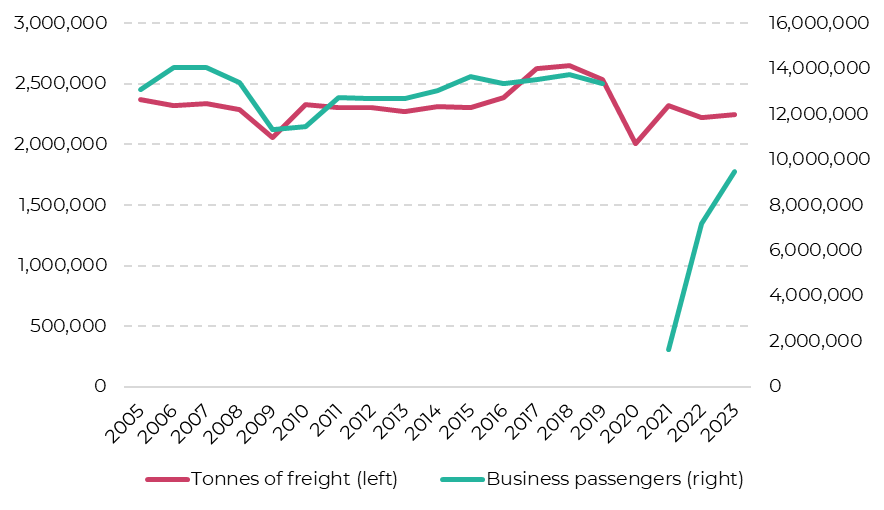

We need to go back to basics to understand why this is the case. The aviation industry interacts with the technology economy in many ways, but it is less complicated in the UK. Despite a strong increase in total passenger numbers in recent years, there has been no net increase in commercial air travel use for almost 20 years, nor has there been an increase in the weight of air freight carried (Figure 1). This is unfortunate because research commissioned by the Department for Transport showed that the growth of this passenger group is crucial to achieving the benefits of wider growth. Holiday travel is the only option.

Figure 1: Annual air freight volume (tonnes) carried at UK airports and number of business travelers

Source: Civil Aviation Authority and ONS Travelpack

The planned expansion of Heathrow, Gatwick, and Luton airports will accommodate around 70 million additional passengers at peak times. Of those two-thirds, three-quarters (45 to 50 million) will be UK residents people leaving the country. While air travel is getting cheaper, domestic holidays, accommodation, and overland travel remain prohibitively expensive, leaving many hard-pressed households with little choice. 25-50% of travelers say “cost” is essential in deciding whether to stay in the UK or travel abroad.

The lack of VAT and fuel duty on air travel further strengthens the case for air travel, with severe consequences. In the decade before the pandemic, the share of annual household spending on international travel had almost doubled. This led to reduced spending on high street and domestic tourism, both of which have declined (which, incidentally, slowed growth). The biggest losers in this exchange will be regions outside London and the South East. Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, domestic tourism boomed, bringing new spending to the long-neglected areas of England. Inspired by this potential (and in line with the “leveling up” agenda), the previous government’s 2021 Tourism Strategy aimed to sustain this trend in the longer term.

Those ambitions have now vanished.

UK domestic tourism has declined for two years since its 2022 peak, contributing to precisely the stagnation the Chancellor fears. At the same time, UK residents flocked abroad in record numbers, bringing home their hard-earned money. New NEF analysis suggests that travel to Mediterranean holiday destinations and the Canary Islands will hit new records in 2024. On our top 20 direct routes, passenger numbers increased from a peak of 52 million in 2019 to 56 million last year.

The last economic line of defense for the proposed Heathrow expansion plans is the weakest. Many want to strengthen Heathrow’s position as a hub, which means attracting “international” passengers connecting in the UK. These passengers stay in the UK for only a few hours, leaving little economic value. And the airlines don’t pay air passenger duty, so the benefit to the Treasury is minimal. However, their flights are part of the UK’s climate responsibility. Transit passengers are a boon to airports, airlines, and the largely foreign-owned companies that own them, but they are of little value to ordinary people.

Today’s decisions about airports reflect the desperation of a government that seems more interested in looking suitable for a select group of wealthy international investors than any real improvement in the economic outcomes of local communities across the UK.